It took an act of Congress, but within the next 18 months, NHTSA is supposed to promulgate a new law compelling manufacturers to implement an automatic engine idle shutdown for keyless ignition vehicles. In two months, NHTSA is supposed to submit a report on anti-rollaway technology to Congress. In the meantime, some manufacturers have already implemented some of these measures. Using internal documents unsealed in litigation, The Safety Record examined how it all went down – in opposite directions – for one major automaker.

The Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act requires NHTSA, after dithering for a dozen years, to write a rule requiring keyless ignition vehicles to be equipped with an automatic engine shut-down feature to prevent carbon monoxide poisoning, and to explore a solution to the rollaway problem. In the interim, some automakers have responded to the latter with automatic-park or automatic electric parking brake countermeasures, and some have equipped their keyless vehicle with automatic engine shutoffs. But the implementation is spotty across the fleet, and few address both. The Safety Record offers the inside story of how one automaker embraced a solution to the rollaway problem, but rejected a fix to the CO danger – making the case for regulations that provide equal protection to all vehicle owners.

The Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act signed into law by President Biden on November 15, 2021 set the clock ticking at the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) to take up – and partly finish – a job that it began more than a dozen years ago: address the increased risks of carbon monoxide poisoning and rollaways posed by keyless ignition vehicles.

By November 2023, the agency is required to promulgate a rule requiring automatic engine shutoffs in keyless vehicles with internal-combustion engines. By this November, NHTSA is required to finish an evaluation of technology to prevent keyless ignition vehicles from rolling away, and present it to Congress with recommendations for further study or action.

Whether NHTSA actually completes these actions by the legally prescribed deadline – and believe The Safety Record – there are no guarantees, is up for grabs. NHTSA has blown so many of them it has been sued by the Specialty Equipment Manufacturers Association, state attorneys general, and the Center for Auto Safety, and prompted Congress to request the General Accounting Office to investigate.

Back in 2009, when NHTSA approached SAE International to gather representatives of industry to write a voluntary standard for keyless push-button designs, only a small percentage of the U.S. fleet had keyless ignitions as standard equipment – about 11 percent, according to Edmund’s. Nonetheless, keyless ignition technology was widespread enough to reveal the safety problems caused by changing drivers’ relationship with the key. In the mid-2000s, the underbelly of this convenience feature was just beginning to show. The Toyota unintended acceleration crisis, in which Toyotas with a drive-by-wire system sped out of control – sometimes at highway speed – showed that drivers were unaware that holding the On/Off button for three seconds was required to shut the engine off while the vehicle was racing down the road.

Owners of keyless ignition vehicles exiting with the key fob, lacking any clear indicators of the engine state, were frequently surprised upon return to find their vehicles still running – or out of fuel. This condition was enhanced by several design characteristics of keyless ignitions – and aided significantly by NHTSA’s 2006 redefinition of a “key.”

Since 1991, Federal Motor Vehicle Safety Standard (FMVSS) 114 Theft Protection and Rollaway Prevention has required that vehicles with automatic transmissions with a Park position must have a key-locking system that prevents removal of the “key” unless the transmission is locked in Park or becomes locked in Park as the direct result of removing the key. When automakers began to implement push-button ignitions with key fobs in the late 1990s, FMVSS 114 was decades old and written for a mechanical ignition. In 2006, NHTSA revised the definition of the key from solely a physical object to include the electronic code used as the vehicle’s unique identifier in these new keyless systems. This change created a loophole that automakers were able to exploit to technically comply with the standard, even as it created a fleet of keyless ignition vehicles that allow drivers to turn off the engine without putting the transmission in Park, and exit with the key fob, leaving the vehicle free to roll.

In this scenario, many vehicles automatically change the ignition state to “Accessory” Mode. This keeps some electrical functions enabled and the “key” (the invisible code) remains in the vehicle ignition module. Drivers are largely unaware that this is occurring. He or she regards the key fob as the key (which is reinforced by automakers descriptions in owner’s manuals and in-vehicle alerts), and believes that if the key fob is in hand and out of the vehicle, the transmission must be in Park. Some automakers included information about the transition to Accessory mode in dense owner’s manuals; some did not. The in-vehicle alerts automakers use to encourage drivers to shift the vehicle into Park are typically low decibel, indistinct chimes that stop in seconds and fail to adequately alert drivers who are often already out of their vehicles.

The first publicly acknowledged carbon monoxide deaths occurred in 2006 involving a Toyota Avalon unintentionally left running in an attached garage.

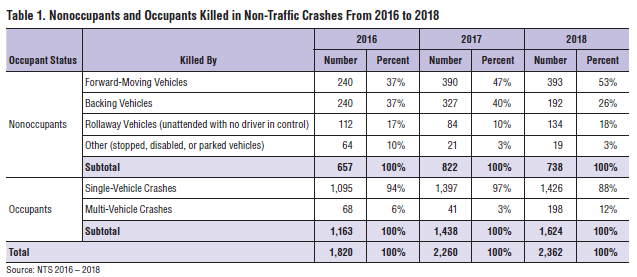

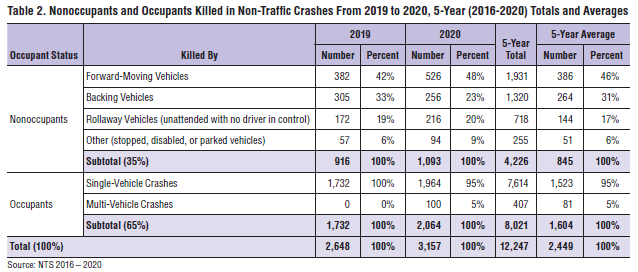

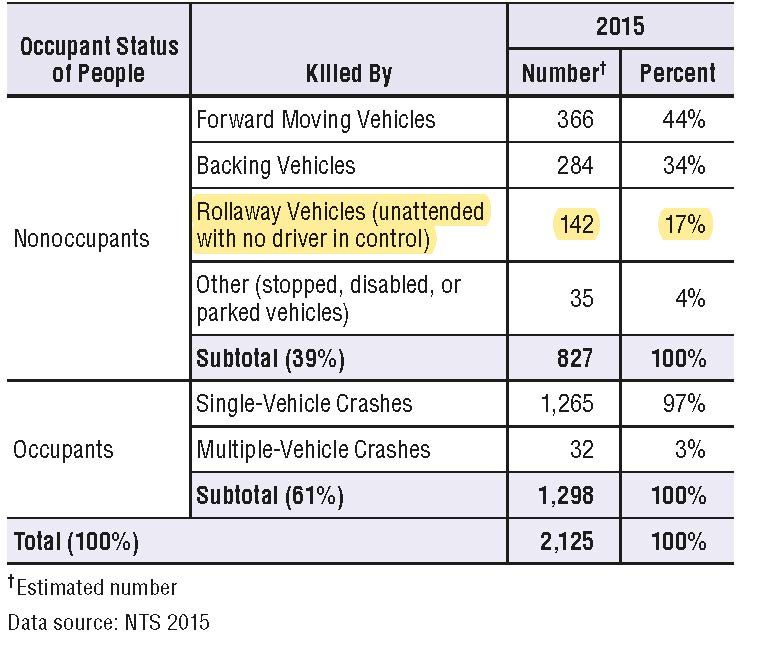

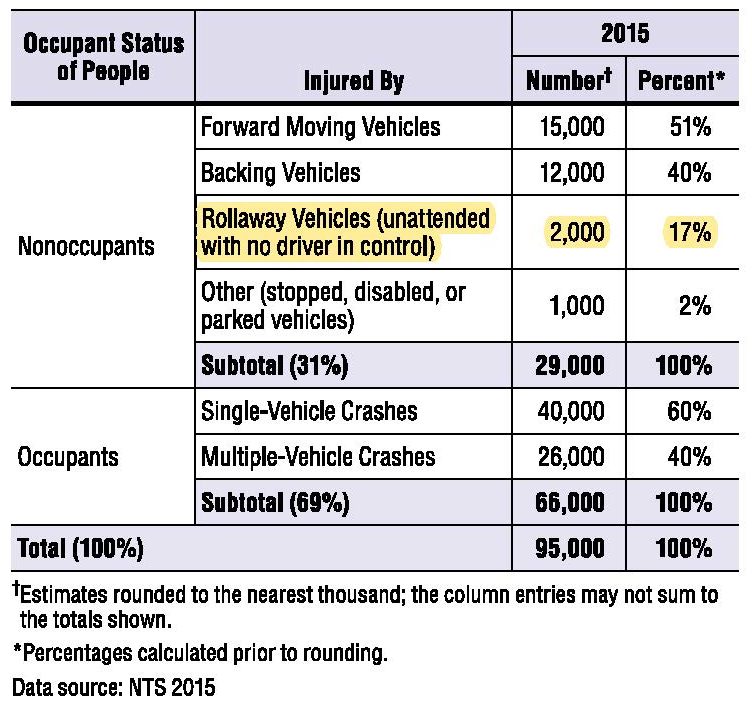

Vehicle rollaway is a persistent problem that NHTSA has estimated causes at least 150 deaths and 2,000 injuries annually in the U.S. In 2007, NHTSA got its first consumer complaint about the potential for rollaway in a keyless ignition vehicle:

“I do not own the 2007 Lexus ES 350 or the Toyota Camry but in the course of test driving both of the vehicles, I was shocked to discover that the “start/stop” button defeats the older ignition key interlock system. In the older keyed ignition system the car must be in park to turn off the engine and remove the key from the ignition. In the 2007 models of Lexus and Camry the engine can be turned off with the vehicle in drive simply by touching the brake–there is no ignition key to place in the steering column.”

The manufacturers failed to heed these warning signs, relying on audible or visual alerts that were often not perceived or understood by the driver. The Recommended Practice released by the SAE Keyless Ignition Controls Sub-Committee in January 2011 was so lame, the agency published its own Notice of Proposed Rulemaking to amend FMVSS 114, Theft Protection and Rollaway Prevention. But NHTSA’s solutions weren’t much better. The agency pointedly eschewed any requirement that keyless vehicles have an automatic engine idle shutdown feature, because drivers might want to leave their vehicles running for long periods of time to keep their pets comfortable – never mind that in the past, NHTSA considered an unattended idling vehicle to be a safety hazard. A technological solution to preventing rollaways had been marketed to OEMs since 2010 by supplier ZF TRW in the form of an automatically applied electric parking brake, but EPBs were not widespread at the time. So NHTSA also proposed audible warnings – but loud enough to break through the fog of a distracted driver – 85 decibels, also loud enough to garner an enormous pushback from manufacturers, petrified of annoying customers.

Manufacturers were steadfastly opposed to the NPRM, accusing NHTSA of pushing a new regulation without doing adequate research to justify this change. Meanwhile, as they helped write the SAE RP and joined the protest against the NPRM, Ford and GM were designing their own automatic engine shutdown features, quietly released in calendar year 2012 for model year 2013 vehicles. In 2019, Toyota implemented an automatic engine shutdown feature in the majority of its MY 2020 Toyota and Lexus badged models.

Today, keyless push-button ignitions are ubiquitous – 91 percent of new vehicles had this design as standard in 2019. Ford, Toyota and GM have all implemented a timed automatic engine shutdowns. Typically, these shutdowns kick in after 30 minutes to an hour, with a warning to the driver that it is about to occur and a mechanism to continue idling. But this feature was not adopted as a safety measure wholesale by the industry. And drivers are still dying from carbon monoxide poisoning in keyless ignition vehicles – with recent incidents occurring in Missouri, Florida and Georgia in the last several months.

FCA: A Leader and a Laggard

The story of Fiat Chrysler Automobiles approach to these keyless ignition hazards, provides an excellent illustration of how technology can provide robust prevention from keyless ignition-related death and injury – and why it was necessary to pass a law compelling automakers to do so.

This narrative was constructed, in part, from FCA internal documents found in unsealed exhibits in Lawson v. FCA. The 2019 case, filed in a Virginia federal court, sought to hold FCA accountable in the July 2017 death of Lee Trinkle Lawson, who succumbed to CO poisoning, after inadvertently exiting his 2016 Dodge Journey with the engine running and the key fob in his pocket. The vehicle idled in his basement garage, as Lawson went upstairs into his home and was later overcome by fumes as he slept. In August 2021, Chief U.S District Michael F. Urbanski granted FCA’s motion for pre-trial summary judgement, ruling that the 2016 Dodge Journey met federal safety and industry standards, and that the Plaintiffs failed to provide sufficient evidence that consumers expected a keyless ignition vehicle to automatically shut down if the driver neglects to do so.

In the late summer of 2013, engineers at Chrysler Group LLC, now Fiat Chrysler Automobiles (FCA), were responding to the rollaway and the carbon monoxide hazards in two different ways. The company was about to introduce the new Jeep Cherokee as a 2014 model year, equipped with Safehold, a software-enabled feature that automatically activates the Electronic Parking Brake (EPB) to prevent rollaway if the driver exited an unsecured vehicle. According to FCA:

Safehold is a safety feature of the Electric Park Brake System that will engage the park brake automatically if the vehicle is left unsecured while the ignition switch is in RUN. For automatic transmissions, the park brake will automatically engage if all of the following conditions are met:

– The vehicle is at a standstill

– There is no attempt to depress the brake pedal or accelerator pedal

– The seat belt is unbuckled

– The driver door is open

At the time Safehold was, and continues to be, one of the very few thorough rollaway countermeasures designed to work any time the driver attempts to get out of a keyless ignition car without putting the gear selector in PARK.

The Safety Record can tell you that people are run over by their own vehicles with surprising and depressing regularity. Drivers get out of their vehicles in the firm belief that the sequence of exit actions executed flawlessly thousands of times prior was once again successfully completed. Except for the time, in haste, or in the midst of all the distractions of modern life – and absent any clear feedback from the vehicle, in the form of creep torque or a significant and immediate warning — that they neglected to put their vehicle in Park.

Sometimes they have turned the engine off; sometimes they have left the engine on intentionally – to keep the air-conditioning running, for instance – or unintentionally. The torque to the wheels when a vehicle is idling in a drive gear on an inclined surface or the tires are in a parking garage seam, for example, can hold the vehicle quietly in place. Rollaways ensue when someone reaches in and shuts off the engine and the torque holding the vehicle in place is removed, or in some instances, when the engine idle increases to support A/C, for example, the little added power can be enough to get the vehicle over an uneven surface. Rollaways often happen so fast, that the audible alerts that most manufacturers use, which sound much like every other alert in the vehicle, give drivers no time to understand the message the vehicle is trying to convey — much less take action.

So many of today’s vehicles equipped with EPBs or electronic shift selectors capable of automatically shifting the vehicle into PARK if the driver doesn’t are only programed to work under narrow and discrete conditions. For example, most automatic engine start-stop features, in which the engine is turned off during temporary stops – such as at a traffic light – and then enabled when the driver depresses the accelerator to resume travel, automatically apply the EPB if the driver attempts to get out of the vehicle while the vehicle is stationary while in automatic start-stop mode. Many vehicles automatically activate the EPB after the driver has put the transmission in PARK. Others are only activated if the engine is turned off while the transmission is not in the PARK gear.

Safehold has always stood out as a design that could avert a disaster following an easily made mistake. It really had no peers in 2014 model year vehicles.

Around that same time, an FCA human machine interface engineer Lori Rodner was finishing up a Design for Six Sigma (DFSS) project addressing drivers inadvertently leaving a keyless ignition vehicle running. DFSS is an engineering design process comprised of specific steps to improve processes or remove defects. At the time, FCA was pushing for its engineers to become trained in the Six Sigma process and complete one project using the DFSS approach. Rodner testified that as an HMI engineer there weren’t many “meaty” issues, but she had heard anecdotally about drivers mistakenly leaving their vehicles running, and decided to pursue the issue to obtain her Six Sigma “green belt.”

In fact, FCA had gotten complaints going back to 2010 from consumers who left their Chrysler or Jeep running and thought that was a dangerous design. For example, in August 2010, a Jeep owner in San Jose, CA called Chrysler’s customer care line to relay her experience:

“I made a mistake today that I walked away from my 2011 Jeep Grand Cherokee Overland after lunch. I didn’t realize that I didn’t turn off the engine before I walked away going back to work in the office. 4.5 hours later, I was ready to go home. When I got close to my Jeep, my Jeep was still running 4.5 hours later without any key close by and without any driver inside. Can you imagine if I parked my Jeep in my garage (instead of outside parking space) running for long hours? It is not safe, and we didn’t expect it could happen. Can you explain why this is allowed? I need some kind of explanation, please. I am scared now.”

In August 2011, the owner of a Jeep called the customer assistance line to report a close call:

“[S]he parked her vehicle in the garage at her home and turned off the key and went in the house. Customer states that her carbon monoxide detector went off in her home, and went out to the garage and her vehicle was still running, and the gas tank was empty. Customer states that the fire department was called, and the carbon monoxide levels were too high in the house, that the fire department advised customer to take her family (7 people) to a hotel for the night.”

Another characterized the vehicle running without the key as “something wrong with my car. That Dodge, Chrysler believes that it’s normal … to me it’s a safety issue.”

And contrary to the judge’s conclusions about customers’ expectation that the engine would automatically shut off, these complaints also showed that, in general, FCA customers, dealers, and customer care agents did not understand how a keyless vehicle with a pushbutton ignition would behave if the engine was running and the fob was no longer in the vehicle. Many assumed it was a proximity device, and would automatically shut off at some point.

For example, in June 2011, one customer called to report that “she took the key off from the ignition and the vehicle was still running and was taken it in to the dealer for diagnosis. She said that she was informed that the vehicle can be running without a key up to 100 yards.”

Another example:

“Customer had an inquiry about the distance between the vehicle and the fob for the vehicle to turn off. Agent advised customer per owner’s manual after 30 minutes of activity the vehicle should shut off. Customer states he was away from the vehicle for over 3 hours and a ½ miles away and the vehicle was still running. Customer states he had the keyfob in his pocket…Agent found the information required. The approximate range for the key fob is 300 ft. (91m).”

In other cases, the customer service representative told a keyless ignition vehicle owner that the engine would automatically shut down at some point:

“The agent explained to the customer that the vehicle all ready [sic] has a 15min automatic shut off. The customer states that the issue is would it really shutdown. The customer states that he is concerned that the vehicle will not shut off he will try the 15min interval. Agent told the customer that according to the owner’s manual it will shut down.”

“The car is so quiet. I could not tell it was running when I went in the grocery store the other day, and locked the door without turning off the engine. Luckily, I had the key. Is there a backup in case I forget to turn off the car? Not used to the button method just yet. Will it shut off after so many minutes on its own? Thanks. Dear Elizabeth: Thank you for contacting the Dodge Customer Assistance Center regarding your 2012 Charger. According to your owner’s manual on page 362: NOTE: If the ignition switch is left in the ACC or RUN (engine not running) position and the transmission is in PARK, the system will automatically time out after 30 minutes of inactivity and the ignition will switch to the OFF position.”

“I have the keyless enter and go. The key fob was in my pocket when I left the locked running van, which I was not aware that the van was running. I would be nice if there was a way to set a maximum running time like there is for remote start. Dear Terry: Thank you for contacting the Chrysler Customer Assistance Center once again. I have received your most recent response and posted it to your file. According to you owner’s manual I believe that your engine should have stopped running after a designated period of time.”

Out of 47 discrete keyless complaints in the exhibit, there were 17 instances in which FCA provided a substantive response to a consumer’s question about how the keyless system works. Twelve of them contained incorrect information.

In September 2010, NHTSA met with FCA to discuss keyless ignition vehicles and the complaints it had been receiving. Its top three: Distracted drivers shutting down their vehicles without putting the transmission into Park, drivers putting the vehicle in park but leaving the engine running, and drivers not knowing how to shut the engine off at high speed – a panic stop. NHTSA itself was in the process of deciding on whether to amend FMVSS 114.

According to internal emails, in 2011 FCA had briefly and preliminarily considered adding an automatic engine shutdown or more salient audible warnings, such as an external chime. But the idea of an automatic engine shutdown didn’t go very far, and the external chime was ditched as too costly.

Engineering Manager Neil Borkowicz explained it this way to a colleague in an email: “We talked about the chime here at Chrysler but no one in vehicle development at the time wanted to pay for a $5 external chime – the issue was smaller at that time.”

In 2012, Rodner gathered a team of 14 FCA staffers – including participants from HMI, Safety, and Regulatory offices, and electrical and ignition engineers – to study the problem of drivers inadvertently leaving their keyless ignition vehicles running, to propose solutions, and to make design recommendations. The problem, Rodner noted in a presentation, was tied to the rise of keyless ignitions, the lack of obvious cues that the engine was still running, quieter engines, more distractions, and busy lifestyles.

They took a multi-pronged research approach that included user surveys of behaviors and attitudes, benchmarking, and an assessment of the efficacy of vehicle warnings. One of the group’s first steps was to conduct an in-house survey of keyless ignition vehicle drivers who had inadvertently left their engines running. The survey was only directed at keyless ignition vehicle users who had inadvertently left the car running, and thus did not measure the prevalence of these incidences relative to all of the keyless ignition vehicle owners. The survey asked questions about the circumstances of the incident, where the “key” (meaning the fob) was located, how many times had it happened and a description of the driver’s feelings about it. An email sent to FCA’s Auburn Hills employees immediately garnered 160 responses, eight personal visits, and six phone calls. Eventually, the team heard from more than 300 employees.

The responses allowed the team to get a pretty good idea of the factors that made it easy for users to make this error. They used the survey results to develop customer “I want” statements about their keyless ignitions, and identified the main customer “wants.” They then supplemented the in-house data with a survey conducted via iCommunity, an on-line Consumer Research site, and another targeted to owners of Chrysler keyless ignition vehicles. In total, they garnered 599 responses. These indicated that the three things customers wanted from their keyless ignition vehicles were: a clear indication from the vehicle that the engine is still running when they are exiting, confidence that the engine is off when they think they’ve turned it off – even when distracted or in a hurry, and a clear indication that the engine is not running, each time they turn off the vehicle.

Other aspects of the research projects included: An internet search of keyless ignition incidents in which drivers complained about inadvertently leaving their vehicles running; a Vehicle Chime survey which benchmarked the alerts found in 21 of their competitors’ keyless ignition vehicles from the 2010-2013 model years; and an analysis of internal customer complaints gathered from FCA’s Customer Assistance Information Reports (CAIRs).

For the chime survey, 77 employees rated the salience of the interior and exterior alerts in seven competitors’ models. The Hyundai Genesis got the top rating, but testers concluded that “although the Hyundai Genesis fared much better, 7.0 and 5.5 respectively, the chime alert was not effective in either situation. Comments included: not loud enough, not long enough, don’t know what it means, not sure where sound was coming from, would not notice if distracted/hurried.”

The CAIRs review found 31 total keyless complaints. FCA’s Mike Schutter, who did the CAIRs key word search said “A majority of customer calls are in conjunction with a request for goodwill assistance, whereas these cases were, in general, just notifying us of this and suggesting ways to improve it, so having 31 in a year is pretty significant.”

To brainstorm solutions, the group conducted a Pugh analysis (A basic decision matrix often used in engineering in which a set of options are scored and then summed to gain a total score which can then be ranked.) The solution had to be effective at preventing people from leaving the engine running when they were in a hurry or distracted, was not annoying, and allowed the driver to leave vehicle running when desired. The Pugh matrix considered whether the possible solution was effective in all lighting and noise environments, could be applied across the fleet for both manual and automatic transmissions, was intuitive, and met regulatory requirements. The analysis’ final recommendations included adding a Cognitive Cue each time engine is turned off, a reminder and an automatic shut-off feature.

The group also recommended that in the future, FCA study the implementation of vehicle logic to avoid a rollaway scenario using such countermeasures as Automatic E-shift to Park or Electronic Park Brake activation.

In summing up the critical lessons learned, the team stated:

- “New technology creates new unique issues. Need to fully validate new technology with special attention to analyze and protect for human error.

- Following competitive set actions may not lead to the best customer solution.”

Despite the work of this team identifying that a significant portion of drivers inadvertently left their engines running, that their customers expected the vehicle to turn itself off, and would support such a feature, the idea of implementing an engine idle shutdown never resulted in a company policy change.

In November 2013, Borkowicz explained that warnings were insufficient to catch the attention of a distracted driver, but an automatic shut-off shutoff would create its own issues:

The only way to prevent these cases of the car remaining running is to shut it off. As the DFSS points out these customers are so distracted that they do not see or hear that the IP is still on, the radio is on, the car engine is running as they walk away, and in the case of the Asian OEMs, the external chime is going off. This has to be weighed against our usual desire to keep the car running. The option that allows you to keep hitting a:

“continue running” button depends on the person remaining in the car understanding it and acting in the available time, if I leave my 85 year old mother in the car in the middle of winter while I go into a store, I guarantee the car will not be running when I come back. She will be upset that she is cold (not that I would do that). Will we like that complaint any better? Or worse yet, the mom stuck in a snow storm with a weak battery, if she misses hitting the continue button because she turns to her baby crying in the back seat, I am pretty sure she will not be happy either about not being able to get her car going again.”

The idea re-surfaced in 2016, when Muqtada Husain, Assistant Chief Engineer of the Electrified Powertrain group gathered a multi-disciplinary team to discuss it, and expressed skepticism about the wisdom of leadership’s decision to forego an automatic engine idle shut-down feature:

“I assume FCA, being a customer focused organization would have already thought through all aspects of this decision, especially in light of vehicles getting quieter, driver’s [sic] getting more distracted etc. NHTSA current proposal of a warning alarm is not good enough and I am sure in light of various field incidents, some appropriate regulations will eventually get formulated. I may not be aware of all the pros and cons In this case, so it you don’t mind, I would like to schedule a small circle discussion to get myself more educated on why we can’t entertain “auto-off” after 30 minute timer in such cases. Thank you in advance for your support.”

With Husain as the feature’s champion, the MY 2018 Pacifica Hybrid became the first FCA keyless ignition vehicle to have an automatic engine idle shutdown. But the feature did not spread to other carlines.

In contrast, FCA’s rollaway counter-measures spread throughout its fleet, and in addition to SafeHold, FCA went on to implement AutoPark on electronic shift selectors. FCA described AutoPark as “an enhanced securement strategy which places the vehicle in “PARK” if the driver attempts to exit the vehicle before placing the rotary gear shift selector in the “PARK” position.” FCA’s first foray into AutoPark started in 2013 model year Dodge Ram trucks – but only those with the Engine Start/Stop (ESS) technology – a limited-population vehicle. ESS technology automatically shuts off the engine when a driver stops for a traffic light, and then restarts the engine when it’s time to resume driving. In 2016 FCA recalled Jeep Grand Cherokees and other models with monostable E-shifters following a spate of rollaway crashes, adding the AutoPark safety feature by re-flashing the controls with updated software. In 2017, FCA added AutoPark to the 2017 Dodge Ram with electronic rotary style shifters.

The FCA story, shows, in a nutshell, why, absent regulation, safety features are an inconsistent patchwork –from manufacturer to manufacturer and even within a single manufacturer. Engineering managers shepherd to production a particular advancement that makes on to one vehicle, or some other vehicles, or no other vehicles. Another demonstrates quite credibly that its own employees and customers are making a dangerous error with new technology, but the higher-ups aren’t interested in fixing it. The mix of development, production, and warranty costs, negative headlines, positive PR, individual interest, and institutional will influence whether a model stands up to the safety chest-beating automakers are so fond of doing or continues a hazardous design until NHTSA finally makes its move.

Perhaps by the 2024 model year, FCA will address the safety deficits in its keyless ignition designs that Lori Rodner pointed out a decade earlier. And the rest of the “automotive innovators,” as the industry likes to brand itself, can catch up and use now old technology such as EPBs with auto-apply functions to prevent rollaways, or timed engine idle shutdowns to prevent CO poisoning, that should have accompanied the introduction of keyless ignition systems in the first place.